From the Lab Bench to the Business Table

A conversation with Georgia about her journey and experience working in industry, both at Novartis and Charles River Laboratories

In science, there are often two main discussed paths: industry or academia. As someone who will start college in a year, I often ask myself which route I should take.

While I know I have plenty of time to decide, it’s always fun to speculate and think about where I could go. However, whenever I do this thought exercise, many of questions arise that I ultimately cannot answer. Only through experiencing it myself will I know if a route through academia or industry is truly worth it.

There is one other way though to answer all of these questions: talking to people who are already on this journey. There are more pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies now than ever before, and an increasingly number of people are excited about working in these fields. One of the centers of biotech, Boston, has over 1,000 biotech companies alone!

Just like technology witnessed a renaissance with the dotcom era and now the AI era, science, particularly the biotech sector, is experiencing its own phase of exponential growth. Less than ten years ago, in 2015, the biotechnology industry was worth $330.3 billion. Now its worth $1.76 trillion. Now more than ever is the time to learn about what is happening in science and what it is like to work in the field.

For anyone interested in this, my conversation with Georgia offers a perfect glimpse into the life sciences industry.

Georgia’s interest in medicine and science sprouted from her parents, who were both doctors, and her innate desire to run experiments. She described running “experiments” on her older brothers, observing different aspects of their daily lifestyle.

She watched what they ate and how it made them feel, what sports they played and how their bodies reacted, and how much they slept and their behavior the following day. Bill Nye, a super famous science communicator, believed that most people who became scientists knew that they wanted to be one at an early age. While I don’t think people necessarily have a calling to science, Georgia definitely is an example of someone with an innate interest in experiments and the general scientific method.

While she had this keen interest, Georgia hadn’t yet conducted a full-length experiment with proper objective data and a hypothesis. This opportunity arose in high school when she was able to work with a Fitbit to track patients’ recovery after total hip implant surgeries. Instead of subjective observations with her brothers, she was now participating in a proper study. Georgia was able to observe the X-rays of patients and how they correlated with the patients’s progress days, weeks, and months after surgery. This experience was the point where she knew she enjoyed science and the experimental process.

Having this experience so early on was definitely crucial for Georgia as it gave her early exposure to what it means to conduct a scientific experiment. This is something most people don’t experience until college, but getting that early validation that you truly like science is important for when times get difficult and you want to quit. When those moments eventually arise, having experiences where you truly loved science is vital to remember why you chose this path in the first place.

College experience

Combining her love for science and medicine with her skill in math, Georgia decided to pursue engineering in college - a natural choice given her skillset. Georgia attended USC mainly because she really wanted to be in California and get out of her environment in Maine. At USC, she chose biomedical engineering as her major because someone suggested it and said that it was a great major for someone who was good at math and science. I love this story because it shows that people don’t normally have everything meticulously planned. Often times, people pick a path because someone suggested it or because of an impulse; not every decision has to be perfectly rational and calculated.

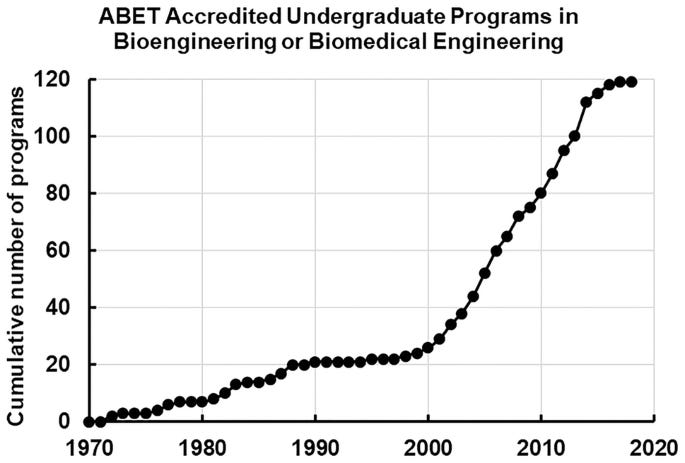

With the biotech boom, biomedical engineering has also gained increased popularity. The major is a perfect combination of practical engineering classes and the premed science-focused classes.

Georgia’s experience at USC was amazing, and she certainly enjoyed her degree. Specifically, she loved having tons of practical experiences such as building an EKG monitor from scratch without any instruction or creating a medical device that had yet to exist and marketing it. These real-world scenarios made classes seem less like school because you are not just learning the material but also putting it into practice. These experiences also give you key intangible skills that can only be taught through experiences like these. Georgia adopted the mindset of “lets do it” and figuring stuff out no matter how impossible the task seemed. These activities also taught Georgia how to push herself and work even when there is no clear solution in sight and she has already been working for hours.

She remembers working in a lab for 6 hours to the point where she was unable to think and yet still continuing to push through. Then when her group finally uncovered the solution, Georgia also recalls how satisfying and rewarding it felt to finally get it. Developing these mindsets and having these experiences are arguably just as important as the hard skills because it is so easy to see something fail and quit, but having the ability to see that failure and push through to find a solution is truly irreplaceable.

“Don’t use failure as an excuse to stop working.”

While everyone develops some set of skills in college, I think what really separates someone is their mindsets and attitude when it comes to approaching problems. Instead of facing challenges and saying “lets fix them tomorrow,” the mental resiliency to continue working when you are demoralized will make you work faster and accomplish more than anyone else.

In addition to her biomedical engineering classes, Georgia took many business courses because she loved the business aspect of science companies. It's important not just to take classes that align with your major but also to take ones that simply interest you. This gives you more dimensionality when going into the workplace because you can bring in different skills and attitudes from those courses. Often, those different ways of thinking is what allows you to come up with creative solutions that other people who just took the courses in the major won’t be able to see.

Listening to this story, Georgia’s college experience seemed perfect. She learned skills while also putting them into practice, setting herself up for success in industry.

Industry Life

When presented with the fork in the road, Georgia chose the industry path. Her reasoning for doing so was that she wanted to work closely with patients, developing therapies that would directly impact them. Unlike academia, where research often focuses on publications that might one day be applied to patients, industry work is far more direct in its contact with patients. Another factor that influenced her decision was that academia often has very limited funding. While prestigious labs do receive a lot of funding, industry generally has a lot more funds at their disposal. Her final reason for was her experience during college at Novartis.

During her final year, Georgia interned at Novartis, one of the largest medical companies developing drugs to treat society’s most challenging diseases. As an intern, Georgia had an incredible time because she felt valued and was treated seriously. Normally, interns are neglected and not taken seriously, but at Novartis, people were eager to teach her, and she was given important work. She was able to present in front of senior scientists and directors and take on significant projects. If a project wasn’t being pushed, Georgia had the freedom to just take the lead and get work done. She was able to try things, find papers that could influence the direction of the research, and it felt like she was a director even at the lowest level of the company. During her research, Georgia did not feel the slightest concerned about money. She could use expensive reagents and equipment without worrying about the cost. Being able to take a project all the way from the lab to presenting it is actually super rare and the fact that she was able to do this speaks to how unique Novartis is.

On top of all this, what was special about her work at Novartis was that it was an industry lab pursuing cutting-edge research. It was essentially an academic lab with industry funding - you could pursue early-stage research without worrying about funds. This is all to say that you are still researching what the company focuses on. Furthermore, your project could get suddenly closed if the company decides to move on to different things they think will generate more profit. This can be viewed in two ways. On the one hand, a Ph.D. definitely offers more stability in that there is little risk of losing your research project; however, having projects suddenly close down means that you end up dabbling in different research areas. As a result, you end up learning a bunch of different topics during your time in industry.

After her internship and graduation from college, Georgia wanted to return to Novartis. However, most positions required at least a masters or Ph.D. This is the irony of the situation: many industry professions actually require a Ph.D., meaning there is sometimes only one path you can take. Because Georgia really wanted to work at Novartis, she found one position that did not require a Ph.D. or masters. Thus, if you truly want to work in industry or do anything else for that matter, be proactive like Georgia and get that opportunity.

Upon returning to Novartis, Georgia gradually took on a larger role, eventually managing other scientists. She moved from the microscopic view of just working on her experiment to now managing others and running a significant part of the project. Novartis was constantly doing collaborations with Harvard and MIT for their projects, so the environment felt like a breeding ground for science. ‘

Hearing about her experience at Novartis made me incredibly excited about the prospect of working there. All the collaborations and opportunities make for a really exciting and innovative environment, especially given that a lot of the projects are in early drug discovery and thus super cutting-edge.

Transition to Charles River Lab

After around 3 years, Georgia switched to Charles River Laboratories, which focuses on delivering solutions to accelerate the development of drugs, chemicals, and medical devices.

Her reasoning for doing so was quite interesting. She called it the “30,000 foot view.” Imagine a cliff: the scientists are the people at the bottom, focused on just their work and tasks in the lab. Then we have the president of the research branch, he sits atop the cliff overseeing the entire research project. Finally, we have the CEO, who sits atop the mountain looking at all the cliffs because he is focused on everything - the overall research and the business strategy of the company. The problem for Georgia is that no one at Novartis had both the business perspective and the boots on the ground research point of view.

What do all of these people do for our organization?

What research areas are making money?

How do we stand up with the competition?

Georgia wanted to be able to answer all of these business questions while still having a foot in the research sector. On top of that, remember how I said that research projects often get closed. Well, with that comes the fact that people often get laid off with the projects closure. Georgia experienced that fate after her area, respiratory diseases, was closed. The major issue for her was that no one knew why the department was getting laid off, not even the director. People were saying it was strategy saying, but what does that actually mean? Georgia really wanted to understand the thought process behind the strategic team and why the company deemed it necessary.

Industry Part 2: Charles River Laboratories

Georgia was able to get those two perspectives at Charles River Lab where she was a strategy analyst for the biologics executive team. Essentially, she worked with the top dogs at the company and was able to understand the backend of what made these companies successful. She learned about the process of hiring and firing, the competition present, and the impact of new technologies on the business. Ultimately, she got to understand why Novartis laid her off and the thought process behind the strategic team.

Finally, she then moved on to being a project manager at a startup inside Charles River Lab called RightSource Solutions Georgia is specifically managing building two quality control labs, making sure everything is running smoothly in accordance with FDA and MHRA regulations. Its very interesting how her job is now fully remote which is a massive change from her work at Novartis in a lab; it really shows the variety of industry experiences that one can have. Her skills at USC now come in especially useful because her job involves a lot of effective planning and troubleshooting when something inevitably does not work out. It goes to show that while hard skills can get you the job, it is those intangibles that come in real handy during your work.

Conclusion

My mission has always been to show the lives of people working in science, both to expose myself to the possibilities and to show others interested in science what you can do. With our understanding and ability to harness biology continuing to ever-expand, there is an increasing need for people to get involved and this space and for them to continue to push the frontiers of science. Stories like Georgia’s are a perfect example of all the promise there is working in this space, and I hope that her story inspires and excites you just as it did for me.